The basic principle which I believe has contributed more than any other to the building of our business as it is today, is the ownership of our company by the people employed in it.

– James E. Casey (founder of UPS)

The last few articles focused on putting in perspective wealth inequality in the US, and looking at the combination of taxation and shareholder capitalism that have led to this concentration. In this article, I’ll highlight my ideas for what I believe would improve the distribution of economic rewards in a more sustainable way.

Corporate form and ownership really matter

So if we think about shareholder capitalism, the nascent efforts toward stakeholder capitalism are one of the critical ways to better distribute the economic creation of society more equitably across society. As the title of this article suggests, one of the potentially underutlized approaches to this can be mainstream private equity (PE). The poster child for this is none other than the original barbarians at the gate, KKR.

Few people know about their Industirals team and Peter Stavros who has been the partner driving their work on this front. He gave a presentation of how KKR arrived at this approach during the 2018 Annual General Meeting for their fund investors – it’s about 25 minutes long, but well worth watching if you haven’t seen it.

The most basic factor KKR had to to overcome is that giving people equity doesn’t make them act like owners. Employees are often skeptical of management and think that the new proposal is likely another sham. A few ways KKR fixed this are:

– They print out physical stock certificates to make it tangible and real.

– They open Fidelity brokerage accounts to hold the stock, with a mark to market so as KKR marks up the value of the company, the employees can see that in their account.

– They also pay dividends as qucikly as they can. Most PE firms do this to get money out quickly and help IRR and also de-risk the investment. But if the employees are getting a check they weren’t expecting, it all starts to make ownership real and the impact is significant.

– Another key factor is they allow employees to invest several thousand dollars alongside KKR on the same terms they do. Given most of the factory floor employees don’t have much savings accrued, this is a meaningful commitment. The genius of this is that even if only 10% of the employees look to increase their ownership through this model, they are bought in from day one to act like an owner as they have hard-earned savings at risk. Not only that, they are more likely to nudge their co-workers to act like owners, because they are, even if they might own fewer shares because they only get the equity granted them by KKR.

– Much more so than other companies, they share the financial performance in greater detail with employees so they start to understand how their work contributes to the success of the firm.

This idea of culture and understanding/education about what being an employee owner means is a persistent challenge. Even within Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs) it can be a challenge, which is why almost half of the agenda at the annual 3-day ESOP conference is focused on communication with employees and the associated development of an ownership culture.

So if KKR has found that this is a win-win, the problem is on it’s way to being solved, right? I think what’s telling is how widely KKR applies this. There are some industries where the employees work is intrinsically motivating (medicine, education, etc.). So it’s unlikely that giving employees equity would affect their engagement or efficiency. To be fair some of these folks are well paid, but in high cost urban areas, they still are unlikely to have sufficeint resources to accumulate much wealth. I think about a nurse or medical technician in NYC or the bay area scraping by on $65,000/year. KKR hasn’t applied this broad-based PE model widely outside its industrials team, as there’s less of a clear win-win. To put more bluntly, their incentives remain maximizing their returns, so if the dilution in equity isn’t overcome by greater employee engagement/efficiency, they won’t do it. This is where tweaks in capital gains can potentially give the PE industry a nudge.

One way I could see nudging firms like KKR to apply this across their portfolio, and also get their competitor PE firms to start to adopt their approach, is to apply the capital gains on firms with sufficeinty broad based ownership at a lower level. There’s more discussion on reforming capital gains to address wealth inequality below, but the PE industry benefits from using capital gains instead of income tax for their carried interest. The tax code is already set up to reward the creation of ESOPs, so this is just extending that principle to PE firms that walk the talk in stakeholder capitalism. The capital gains tax will mirror personal income tax rates, but if your capital gains are from an equity investment where the company had at least 10% employee ownership and that ownership was broad based, the capital gains rate would be the current level of 23%. Again, ESOP legislation ensures ownership isn’t just concentrated in the C-suite but is more equitably spread across the organization, so there’s precedent and framework for defining what qualifies and what doesn’t. This would avoid the situation where 9.9% of the company is given to the C-suite and 0.1% goes to the ‘workers’, which is closer to what happens in most PE investments today. Given there are several thousand PE transactions every year, if this became more widely applied, the inclusion of labor in the wealth creation of capital would start to become material and I believe would make significant progress to reverse the wealth inequality trends of the last 40 years.

Worker Co-Ops and ESOPs

PE isn’t the only approach to broad based worker ownership, but it is certainly the one with the most scale, capital (over $1 Trillion of dry powder at the moment) and infrastructure to move the needle. There are a variety of ways firms use corporate structure to affect wealth distribution, from worker co-ops, to ESOPs. There are variations in these approaches as worker co-ops and ESOPs have been around for decades, and in the U.S. the policy and legal support for these corporate forms is well established. However, their adoption is often relatively small. The number of worker Cooperatives is extremely small in the U.S. (Democracy Collaborative has listed the number at roughly 400 firms that collectively employ less than 10,000 people). Some of the iconic examples here in the bay area are The Cheeseboard in Berkeley, and the associated spin off of Arizmendi association of bakery cooperatives. The latter is named after the Spanish priest who launched Mondragon in Spain after World War II. Mondragon is a collection of worker cooperative companies that employs more than 80,000 people and has over €12 billion in sales. There are other examples of scalable worker coops in other countries as well, but not in the United States. So the ‘success’ stories in the US are smaller businesses that aren’t capital intensive. Given the example of scalable solutions in other countries, this is an area that needs more innovation and ecosystem development to scale, but is certainly worth additional work as another model, especially for firms that may not have the growth profile for many private equity investors.

The legal structure to enable ESOPs was enacted in the early 1970s, with improvements added over the last four decades. There have been more than 10,000 ESOPS over that period, including several that employ thousands of individuals. So relative to worker cooperatives, ESOPs have had more traction in the U.S. When I suggested to several partners at Goldman Sachs that financing ESOPs and looking to this model as a way to address wealth inequality would be a win win for everyone involved, they tended to raise a quizzical eyebrow at me. They then followed up by talking about the painful experiences they remember from firms like United Airlines that offered majority control and ownership to employees in return for significant wage and benefit concessions. When the company went bankrupt (a recurring theme in airlines), the employees equity value was wiped out, and there was a sense that the employees got the raw end of the deal. The truth is a bit more complicated, but it’s fair to say that ESOPs and broad based ownership aren’t always a silver bullet solution for every potential business. But there are thousands of examples where employees have done very well that don’t get the same attention as the few high profile failures. New Belgium Brewing is often held out as a prime example of an employee owned business that has scaled dramatically over the past 15 years.

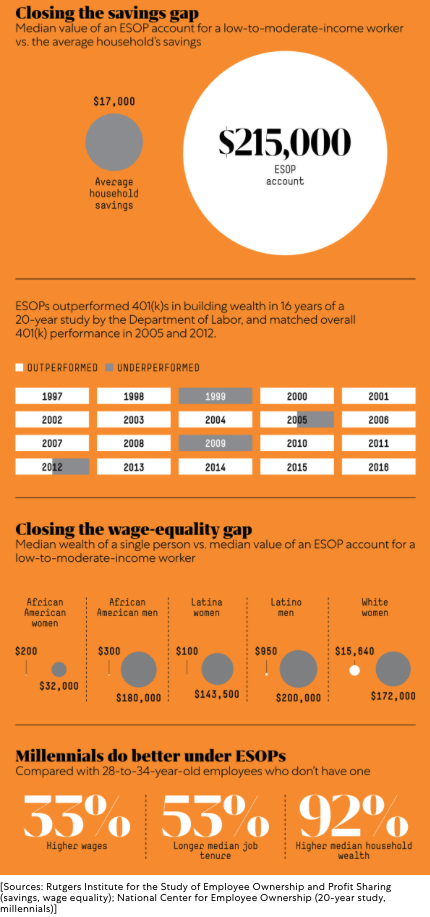

Because there are so many more ESOPs and so many more employees in ESOPs relative to worker cooperatives, it’s easier to get a baseline read on the impact ESOPs can have on individuals’ lives. A 2017 study by the National Center for Employee Ownership benchmarked wealth for individuals in the same industry, but where they worked for an ESOP or they didn’t. Not surprisingly, the graph below illustrates that the ESOP employees had made significantly greater progress in wealth creation than those that didn’t work in those firms. And if you’re paying attention to the Diversity and Inclusion awareness that has arisen related to BLM or gender pay equality, these demographics also do far better under ESOPs.

Fiscal changes can also help

There’s an infamous Russian fable about a poor farmer who finds a genie in a bottle in his field. After he rubs it, the Genie arrives and grants him one wish. His response, “You see my neighbor, he has two cows and I only have one.” The genie then asks, “So you want another cow?” The man replies, “no, I want you to kill one of his cows.” Talking about progressive fiscal reform can seem like this quote in that you’re arguing it’s a zero sum game and you are trying to take from someone to give to someone else. At some level that is true, but more fundamentally, I believe that if the wealthy few aren’t constrained to some degree, the democratic system is perverted by money and power in a way that will allow them to continue to propagate inequitable allocating of society’s economic production. This is most clearly demonstrated in the tax code.

In the last article, I highlighted how most of the tax benefits over the last 40 years have been occurring to the wealthy, largely through asset appreciation. This isn’t to imply that the only tax we need to worry about is capital gains tax for mitigating wealth inequality, but rather the balance of the overall tax system is what leads to dislocations that make an economic system socially unsustainable over time. Fundamentally, the lower taxes on wealthy individuals, capital gains, corporations, and estate taxes have co-incided with the rise of extreme inequality. So expecting the tax system to remain the same and get a different outcome sounds a lot like the proverbial definition of insanity.

For individual income taxes, I do think that having higher income taxes at the larger marginal tax rates is important. This is particularly important for individuals that recognize most of their compensation through income instead of asset appreciation. I can think of hedge fund managers who get 20% of profits in their hedge fund, which is unlikely to be capital gains given holding periods. This is distinct from Private Equity, where the longer holding periods have allowed them to argue that their carry is capital gains, not income. I think the argument PE firms make is a disingenuous argument at best, as the downside is asymmetrical. If the fund loses money, the managers don’t have to pay a penny, and all the losses are borne by the limited partners. So it seems more analogous to salary or bonus where if the company does well, pay can go up, but if the company goes under, the employee doesn’t have to contribute to the deficit.

Raising the highest income tax rate on individuals that get most of their income through asset appreciation is less effective, as almost none if their inflow of cash is considered ‘income’ for tax purposes. But here, we need to look at the capital gains tax as an underutilized approach. We have a progressive income tax, raising the rates on marginal dollars at higher levels of income. But we have one capital gains tax regardless of the amount of the capital gain or the relative wealth of the investor. A progressive capital gains tax can help narrow the gap in wealth by reducing the after-tax compounding of returns to capital versus returns to labor (salaries, etc.) At the very least, at a certain level of capital gains, the tax on the gain should mimic the highest income tax rate. Over time, individuals that have large compensation packages with incentive stock options would find that those are less attractive compared to outright cash compensation, as their after tax outcome will be identical, but the concentration of their wealth in company stock skews the risk of this form of compensation. If they are comfortable with that risk, or even seek it out as they feel the company is massively undervalued or has a long growth trajectory, they can purchase shares and own them outright to have that exposure. Fundamentally, having less of a gap between capital and income taxation will make it harder for individuals to shift their compensation/income to lower tax solutions. This is particularly important for addressing inequality, as individuals without the income or savings to acquire appreciating assets get left behind, while the wealthy get even richer.

Similar to the argument above, I believe that corporate taxation has gone too far in the direction of cuts. The argument that the $1.5 trillion in expected tax reduction for corporations over 10 years would be invested in new capacity that would increase GDP growth is not playing out. With roughly $1 Trillion of share repurchases in each of the last 2 years, corporations have more capital than they can productively deploy. And the upside of the share repurchases is to increase the share price, further accruing wealth to the shareholders (increasingly the top 10%). I already see arguments that we will push companies to relocate to lower tax areas however, I think this is a red herring. Fundamentally, the US is such an attractive and large market, that I don’t think we do ourselves any favors trying to compete in a race to the bottom of corporate tax rates with smaller countries like Ireland and Singapore. Also, as we’ve seen with corporate inversions, this can be stemmed with policy implementations as well. The 2014 and 2016 policy changes reduced the appeal of shifting a corporate headquarters offshore at higher tax rates than currently exist. Even at the peak, only 8 companies completed an offshore inversion in 2012 (falling to only 3 in 2015). So it’s unlikely to be a flood of companies regardless. I’d also point out that if we had more worker ownership of equity, higher stock prices/valuations would benefit workers as well. But until we have more broad based worker ownership, low corporate tax rates largely accrue benefits to the wealthy.

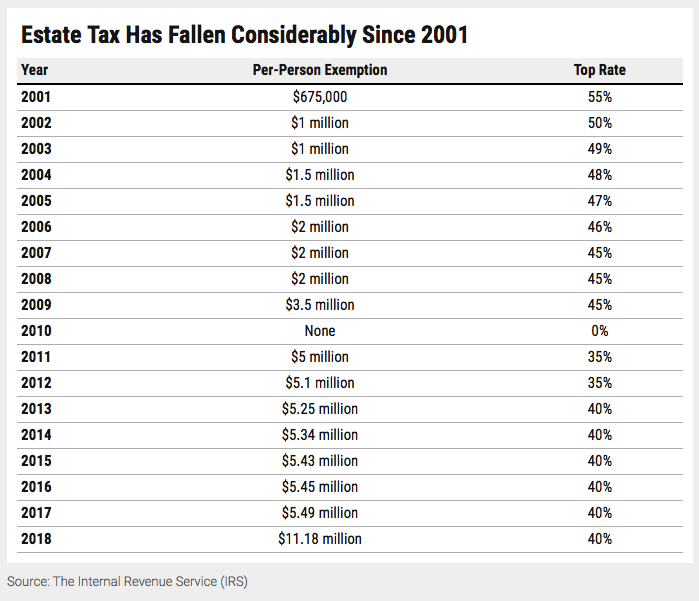

The final tweak to fiscal policy I’d propose is to the estate tax. This is really an effort to make sure that excess wealth isn’t embedded into creating an inter-generational aristocracy that ultimately has all the influence and political control. I have no problem with inheritance per se, but it should be sufficiently modest that it doesn’t perpetuate gross inequality. Two of the challenges of the current system are that the rate and threshold for triggering estate taxes is low by historical standards (the chart below highlights this).

The second challenge is the loopholes that exist to evade whatever rate is set. Over the past decade, it’s estimated that well over $100 billion in estate taxes has been avoided through use of these loopholes. Given that roughly 40% of household wealth is through inheritance, and most of that is at the upper end with very large inheritances, this becomes one of the most progressive taxes for addressing wealth inequality. So eliminating as many loopholes as possible, and reducing the threshold to $10 million per couple instead of per person (basically doubling the rate per couple to $20 million as it exists today) would help.

There are many think tanks and academic resources focused on optimal tax strategies. I particularly like Stephanie Kelton at Stony Brook, the Tax Policy Center at Brookings, Emmanuel Saez at Berkeley, and everyone’s favorite inequality economist Thomas Piketty for anyone wanting to go deeper on these topics.

Thinking in systems is also key

These potential corporate and fiscal changes are by no means the only efforts needed to address wealth inequality. Education is foundational, and if we have inequality in our education system, it will be extremely difficult to make progress in mitigating wealth inequality, let alone continued economic development. However, I do believe the two biggest levers that are not being used effectively today are: 1) Focusing on the policy and additional fiscal nudges that can encourage broader based worker ownership. If the last half-century has shifted the economic rent to capital from labor and made the owners of capital wealthier than the providers of labor, then one solution is to allocate some of the capital of these enterprises to labor. As KKR has shown, in many cases this can be a win win for everyone, making it more likely that when the tide rises, all boats will go up. Or to make that a better analogy, when the tide rises, there are far fewer people standing on the shore getting submerged while more people are on boats that rise. 2) reforming our fiscal policies so that taxes become more consistent across the different ways they are applied so that wealth isn’t shifted to the lowest possible tax rate. This includes harmonizing income, capital gains, raising corporate rates and also having a more progressive estate tax.

I’d end by pointing out that I’ve been extremely fortunate in life, and I have wealth and access to resources to live a privileged life. So increases in taxation and the estate tax are likely to hit my personal pocket book. I’m still wildly supportive of these proposals because 1) I do believe they are morally the right thing to do and 2) if we continue on the path we are on, the likelihood we tear our country apart, likely by force, grows greater every day. So if I ignore the first point, the machivellian in me still thinks it’s extremely important to pursue these policies, as a violent fraying of society likely does more harm to me than the economic inconvenience of higher taxes. So with that, I anxiously await November to see how the policy environment evolves as voters choose the President, Governors and Legislatures for the next 4 years.