Please sir, may I have another?

I suggest to you that increasing the size of America’s economic pie – which can be achieved only if everybody has a seat at the table – is the most important challenge facing our country today.

– William Weld

In a previous article, I focused on the conundrum that capitalism, as it exists today, is both positive in how it has lifted the standard of living for billions of humans, but also challenging in that it has concentrated the wealth in more established capitalist economies. So this article looks at why that seems to have happened, and by understanding that, ways to change the trajectory.

Before launching into that, it’s important to understand two premises I firmly believe. First, markets are amoral. I don’t believe they are good or bad, but rather they are an artificial construct of humans. Indeed, I couldn’t have worked at Goldman Sachs on three different occasions for nearly a decade in total if I didn’t believe in markets. However, the second point is: how you set up the rules will determine the outcomes. I would argue that when the pendulum swings to extreme laissez faire approaches the outcomes are not sustainable for long periods of time. The perverse incentives that mortgage finance laws created led to the 2008 financial crisis as a prime example of this. Conversely, when markets are overly structured and constrained, it starts to look like a centrally planned economy, which historically hasn’t worked terribly well for long periods of time either (e.g. Soviet Union, etc.)

So with these frameworks, it’s possible to see how the rules and approaches over time have led to the current concentration of wealth and associated power into the hands of the few. From there it will be easier to explore alternatives that can lead to a more sustainable society.

It’s about Wealth not Income, but there is interconnection between the two

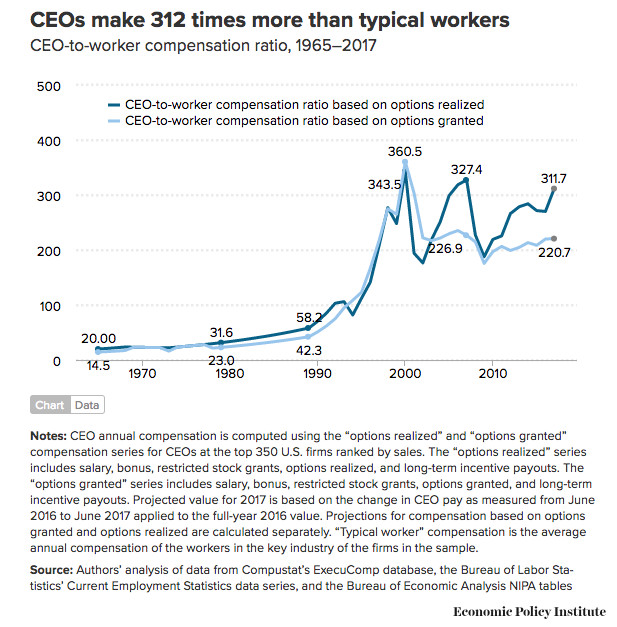

Much of the press over the last decade on this topic of economic inequality has focused on income inequality, with the headline grabbing shift in the compensation of CEOs relative to the average worker in a company. As the chart from the Economic Policy Institute shows, the numbers are indeed staggering with average compensation at large firms increasing from 20x to over 300x in the last few years.

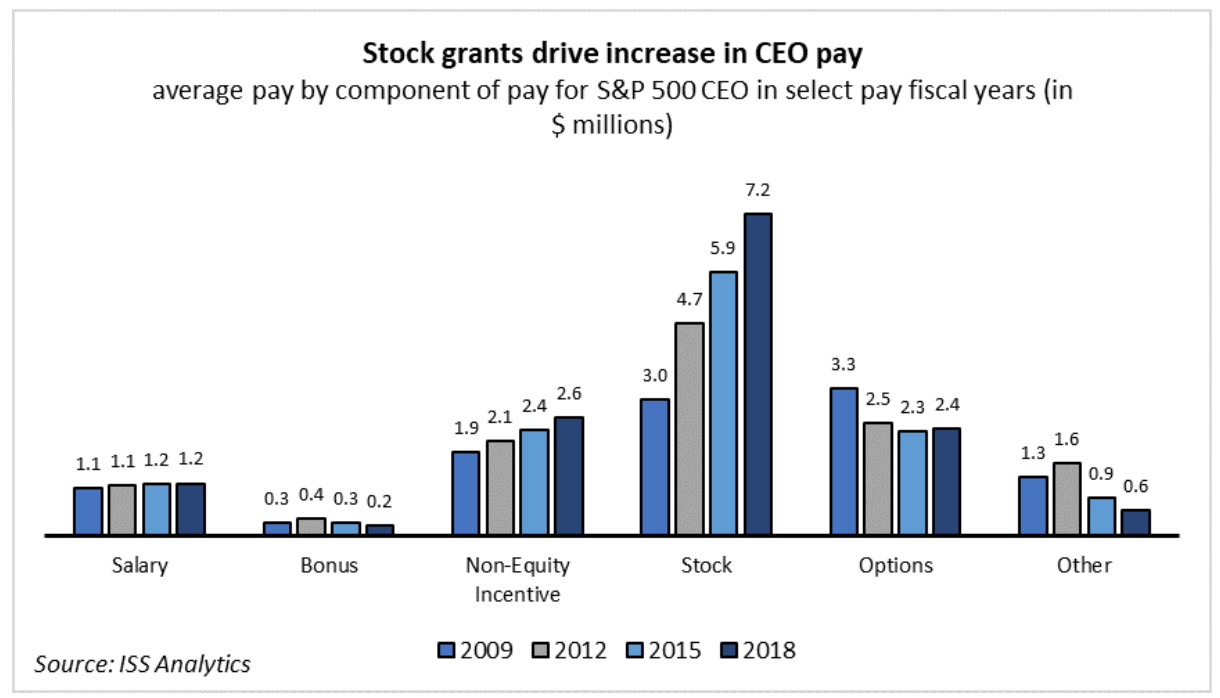

However, this income isn’t all cash. The graph has a huge footnote and talks about the options granted, which is important, as the composition of executive income has changed dramatically over the last few decades. The percentage of executive compensation that is actual cash is typically less than 20% of their compensation. Over the past few decades, the trend has been to pay a majority (in many cases a vast majority) of compensation in the form of either stock options or outright grants of company stock. The graph below from a Harvard Law article highlights this.

You may be asking, so what? Whether it’s cash or stock really doesn’t matter that much, as they are getting very large compensation. The reason it’s so important is two fold: First some companies couldn’t realistically pay out the entire compensation in cash. It’s admittedly a rather unique example, but Tesla has paid Elon Musk billions of dollars in the form of stock, while the cash balances of the company haven’t been large enough to make those payments in cash. There is also the argument that this large stock ownership aligns the executives with shareholders, which is preferable to paying out cash to them that would otherwise be dividends to the shareholders. This argument is why many highly profitable companies that could pay all cash still prefer equity compensation for most of their executive pay. The second reason the mix of compensation really matters is that it typically compounds over time. If you receive options or stock, and the share price increases significantly over the next few years, your compensation has effectively gone up by that increase. So the ownership of corporate equity really matters for wealth accumulation.

Taxation has compounded this…

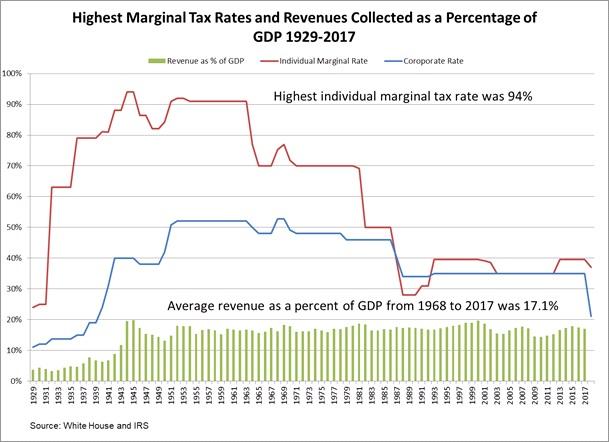

Focusing on income and wealth, taxation plays a complinentary if not more important role. Over the last 40 years, the US tax code has been focused on pursuing the supply-side economics first proposed under President Reagan. The general premise is that if you reduce the tax rate on the wealthiest people (or corporations), the increase in consumption and investment capital will lead to more economic activity, providing more jobs and wealth for those below as well. If the GDP increases more than the decline in the tax rate, government revenues will be higher under a lower tax rate. The chart below highlights how the reduction in the highest marginal tax rate has trended with income tax receipts as a percentage of GDP. The reality is that the government has taken roughly the same share of annual economic output even with lower tax rates (between15% and 20% of GDP but most years roughly 17%).

The supply side supporters (and much of the wealthiest 1%) would argue that in absolute dollars they are still providing most of this funding, so raising the rates on them is unfair as in absolute dollars they are already doing most of the heavy lifting. Although the math makes that true (the 1% pays the same absolute amount of tax dollars as the bottom 95%), the fact that wealth inequality is continuing to get worse, is a counterfactual that indicates that despite this heavy lifting, the tax burden isn’t holding them back. And this is where it is again important to focus on the distinction between income and weath and how that plays out in the tax code.

At a personal level, income comes principally from salaries, interest, dividends, and gains on sales of assets. But wealth is the value of one’s entire balance sheet, which often includes assets that can go up in price far more than personal income. So having an asset that appreciates dramatically (like corporate stock), which you can then sell for a capital gain at a far lower tax than the highest marginal tax rate, means you are able to increase your wealth and disposable cash dramatically even while others have flat income. This is largely the trick that has enabled the 1% to race way ahead of the bottom 99%, or even the next richest 5%. This is also compounded by the delta between the capital gains tax and the income tax rate, famously illustrated by Warren Buffett who thought it was odd that his tax rate (roughly 15% at the time which was basically all capital gains) was lower than that of his secretary, who presumably wasn’t in the top tax bracket, but likely was in middle income tax brackets. However, personal income taxes aren’t the only issue, as corporate tax policy can also compound this problem.

Corporations matter too….

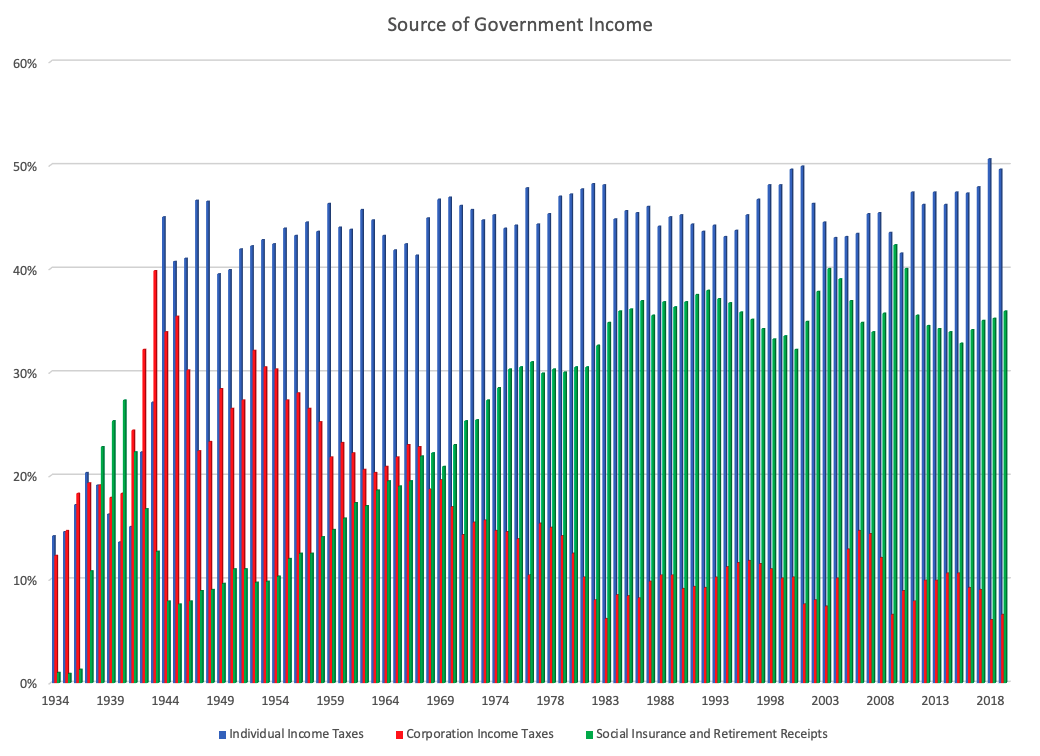

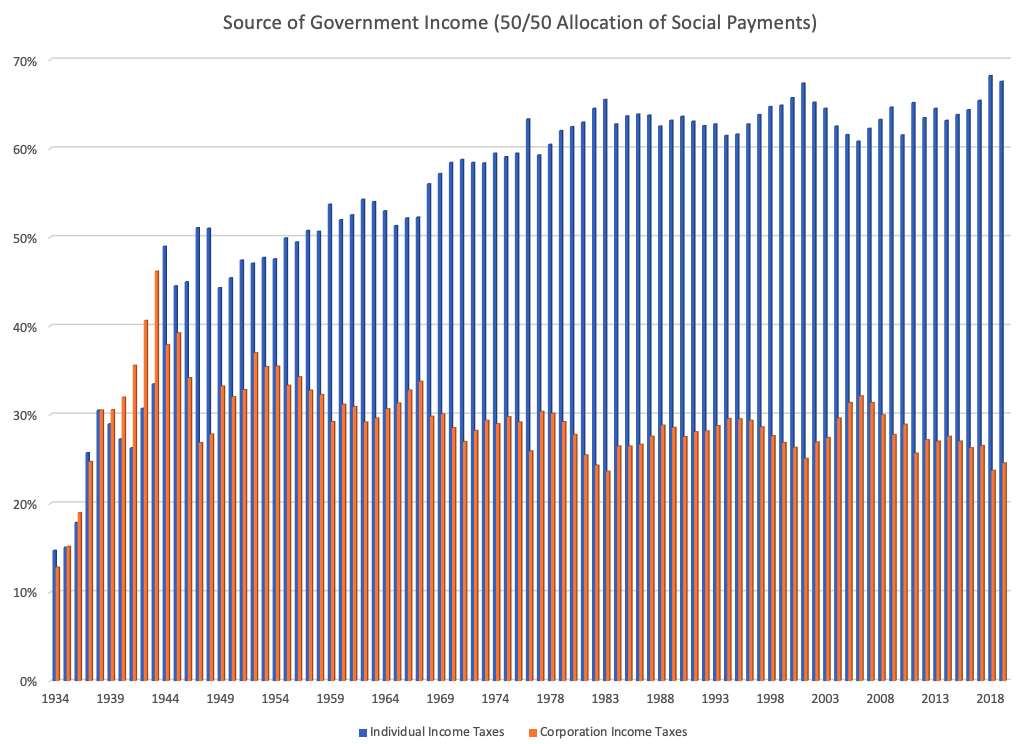

I personally found the reduction in corporate tax rates in 2017 rather hard to explain. I’m cynical on this point and believe companies have largely perfected the ability to lobby for and exploit tax loopholes to avoid paying taxes. But the chart below highlights how much the shift in federal taxation has shifted from a blend of corporate and personal taxes being almost equal percentages of the federal revenue to a reduction in corporate taxes from roughly 30% of government revenues in the 1950s to roughly 6% today (data sourced from the Office of Management and Budget). Admittedly, the payroll tax (social security and medicare payments) is another cost to corporations, but that is also shared by the individuals, so they don’t really skew the relative contributions of individuals and corporations. If you were to allocate the social income (94% of this is social security and medicare, which are shared 50/50 between employee and employer), the graph would look like the one below. So the general trend of increasing the tax burden on individuals over corporations still holds with individual income tax roughly 65% and corporate roughly 25%.

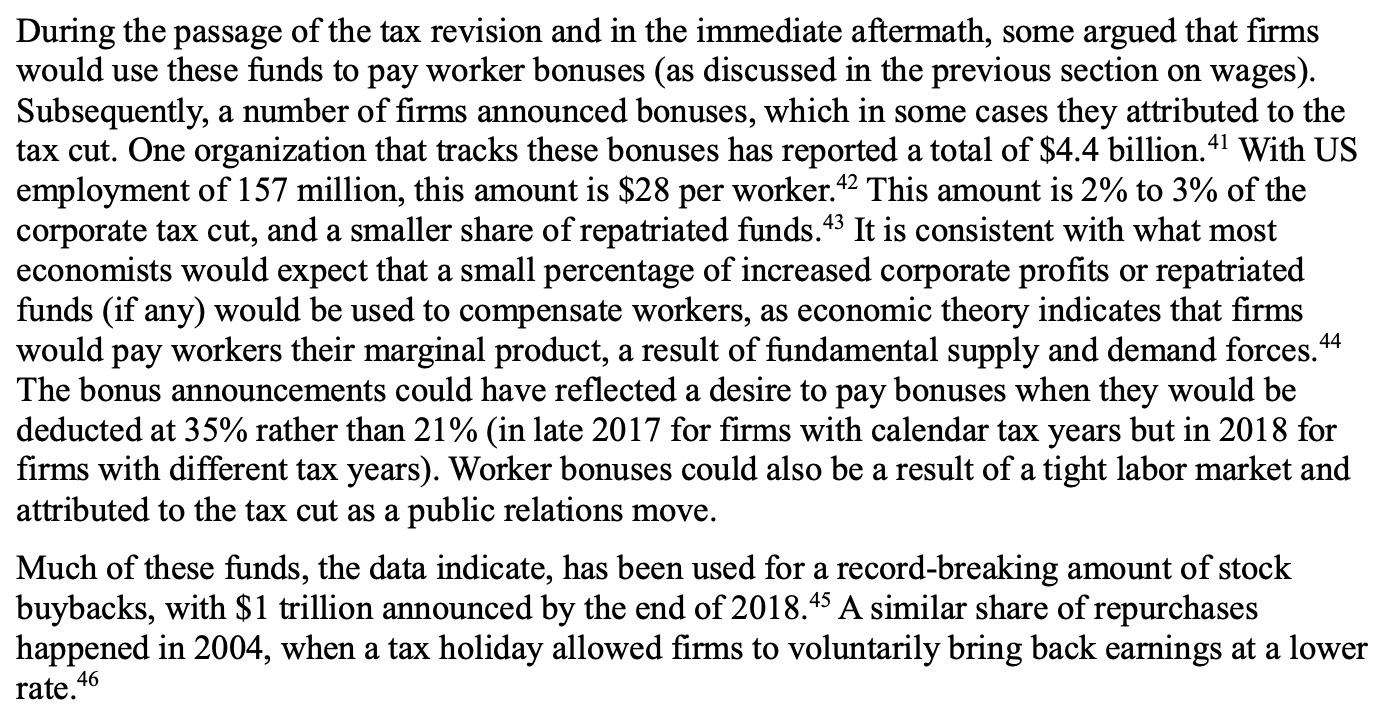

Shifting the tax burden to individuals from corporation is a policy choice to encourage more investment and economic activity. What I find most objectionable about the corporate tax cut is the myth in 2017 is that companies would invest in factories to create jobs, or that companies with larger after tax cash flow would share that with workers. The Congressional Research Service did a survey in 2019 to look at the impact of the tax cuts during 2018 (the first year they were enacted).

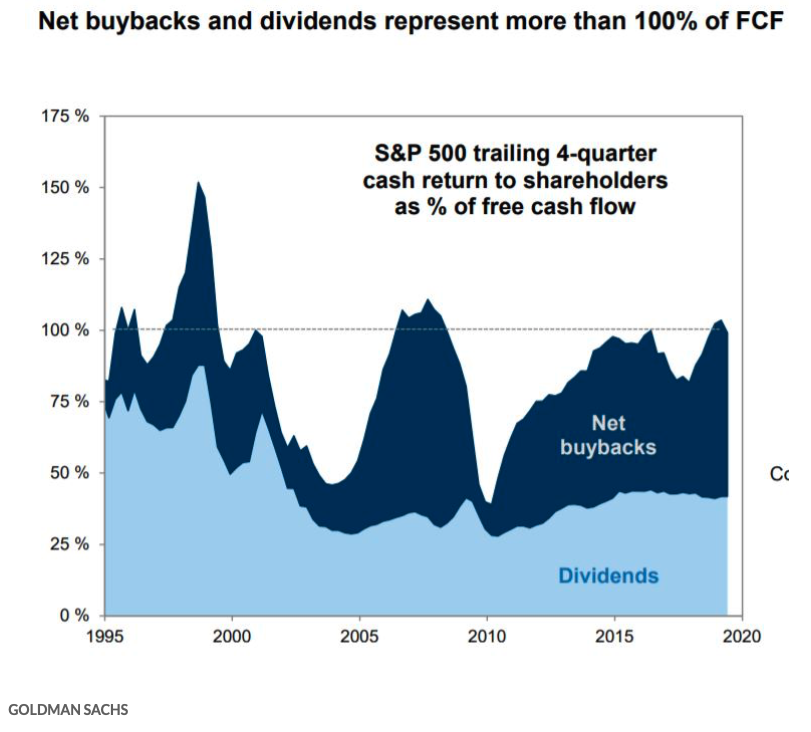

This shouldn’t be terribly surprising as the history of how companies have spent their free cash flow has shown that they often look to return it to their shareholders, either through dividends or share repurchases. Goldman Sachs reported last year that the aggregate return of capital is often greater than 100% of free cash flow, which means the shareholders are getting the economic spoils, while workers, customers and other stakeholders are staying right where they are. Even when it’s not more than 100% of FCF, the vast majority of disposable cash is focused on shareholders.

So if you look at our current tax system, the combination of lower capital gains taxes relative to marginal tax rates and the lower corporate tax rates providing more free cash flow to repurchase shares has significantly contributed to growth in wealth of the top decile relative to the rest of the population, and perpetuated the reinforcing cycle of shareholder capitalism.

Corporate Ownership

To be clear, there is a relationship between income and wealth, in that if you have enough income you can acquire assets that might appreciate. This typically includes stocks or houses and other real estate. As such, the question of corporate ownership is one of the key levers that leads to this wealth gap.

The two trends that contribute to this are shareholder capitalism and concentrated corporate ownership. The discussion about executive compensation with stock and stock options along with the tax code rewarding returning capital to shareholders illustrates the challenge with shareholder capitalism. There’s no shortage of other good articles on the impact of shareholder capitalism, and it’s been interesting to watch corporations shift the rhetoric about this over the past 18 months as they have increasinlgly come under pressure for not valuing other stakeholders (employees, customers, supply chain, commuinty members where they operate, etc.) The optimist would say that corporations have now seen the light and are shifting away from shareholder capitalism, however time will tell if that actually plays out.

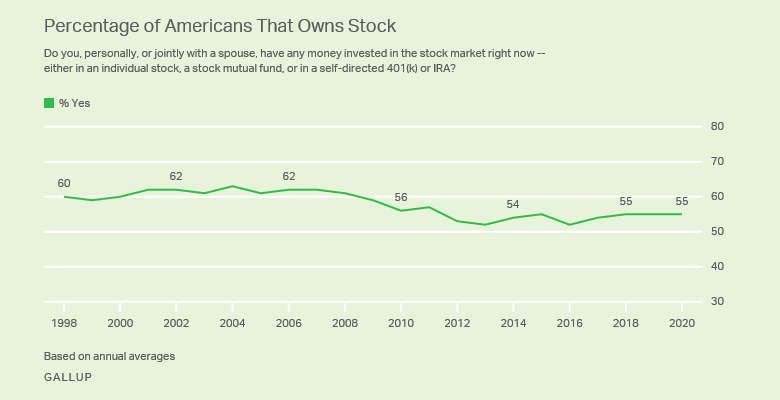

I think a less explored angle is the second item, which is that much of the ownership of these businesses remains concentrated in the hands of half the population and disproportionately the top 10%. The table below highlights how half of Americans don’t own any stocks.

The argument that they have pension plans and the stocks are owned by these large institutional investors largely falls short, as the percentage of companies offering defined benefit plans has fallen to less than 5% of workers in 2019 from more than 60% in 1980. Defined Contribution plans (401(k), etc.) that would be reflected in the stock ownership numbers above have become increasingly popular, but if you think that 60% of workers used to be covered by pension plans and the number that now own stock in either a 401(k) or personal account is now only 55%, de facto the number of individuals with a stake in the economic pie has decreased (some of the 5% still with defined benefit also offer 401(k) so there’s a blend. I personally received a small define benefit pension from my first few years at Goldman Sachs, that in the 1990s switched to a 401(k) as an example. So the 55% will include most of the 5% of the workforce that still has a defined benefit pension).

The other concentrated ownership issue is the rise of private equity over the last 30 years. The middle market (variously defined so a bit squishy, but think of 20-1,000 employees and typically less than $3 billion of company value) is particularly the issue. There are an estimated 200,000 of these businesses in the U.S., and roughly 3,000 middle market private equity transactions every year. So about 1.5% of them are bought and sold among private equity firms every year. This isn’t a large amount, but if you play this out over 15 years, roughly 1/5th of existing middle market businesses have become private equity owned. Another chunk of them are likely to be acquired by larger businesses as well. For the employees, they typically get their salary, but the upside for the value creation of those businesses (equity value) accrues to the PE firms and their Limited Partners (LP). When the LPs of private equity funds were predominantly pensions, you could argue it was accruing to the workers in the form of their retirement accounts, but given how few workers are now part of a pension plan that argument starts to fall short. So if you look at the funders of PE firms, they are increasingly sovereign wealth funds, endowments, insurance companies and the 1%. Pensions (especially public pensions) still remain investors, but the upside of private equity isn’t closing the loop with workers the way it did when more workers were covered by a pension. I further think the Middle Market is most important, as roughly 40% of employment is at these businesses (US Census data), yet they are most likely to be owned by a a sole proprietor (family) or private equity firm. Larger companies sometimes have policies like Employee Stock Purchase Plans to make it easier for workers to acquire some corporate equity, which is rarely in place at middle -market firms.

All of these factors combined have led to a market economy where the rules and incentives have focused wealth in the hands of corporate owners over workers as the growth in corporate value has far outstripped incomes. This explains why executive compensation has shifted to corporate ownership as well as favorable tax solutions to reinforce this at both the personal and corporate level. A series of proposed solutions to address this (without government dictated tax and redistribution) is the topic of the next article.