ESG for most asset managers is a total greenwash and investors need to wake up and realise that their asset managers talk but don’t actually do

– Sir Christopher Hohn, Children’s Investment Fund Foundation

The False Dawn of ESG Investing

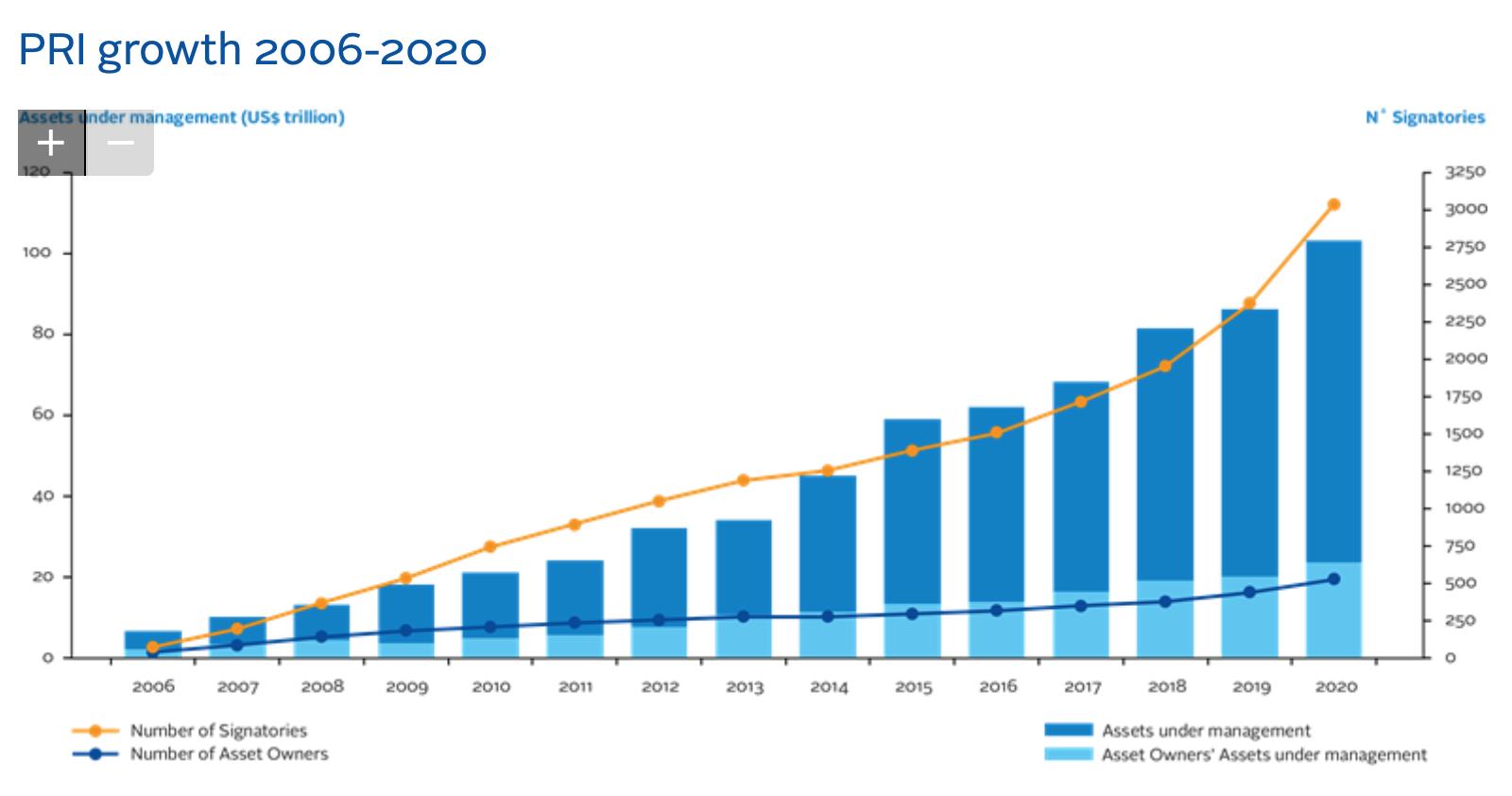

While ESG investing is evolving, most investors have a long way to go. The number of private equity General Partners (GP) that embrace ESG has grown extensively over the years. There’s a range of ways they do this, from writing their own sustainability reports to joining movements like the UN Principles of Responsible Investment (UNPRI). Indeed, the UNPRI has seen a dramatic increase in signatories and committed capital over the past few years (admittedly across all asset classes not just Private Equity).

The interesting question is: why do income inequality, inconsistent corporate governance and scandals persist if firms with nearly $80 Trillion of capital under management are committed to follow UN PRI guidelines? I have a few ideas about this.

First, most ESG standards are relatively toothless. There is not a definitive set of standards that any given company or investor must abide by to declare themselves ESG compliant. The guidelines are often vague and the consequences for not complying usually aren’t real. So, signing up for UN PRI doesn’t really mean much.

Indeed, I know some signatories that fill out the annual ESG questionnaire for UN PRI by only applying purpose-built products for ESG or impact investing, even if that’s a trivial percentage of the total assets under management. So, if you counted only the authentic capital that embraces ESG, it would be a small fraction of the $80 trillion estimate.

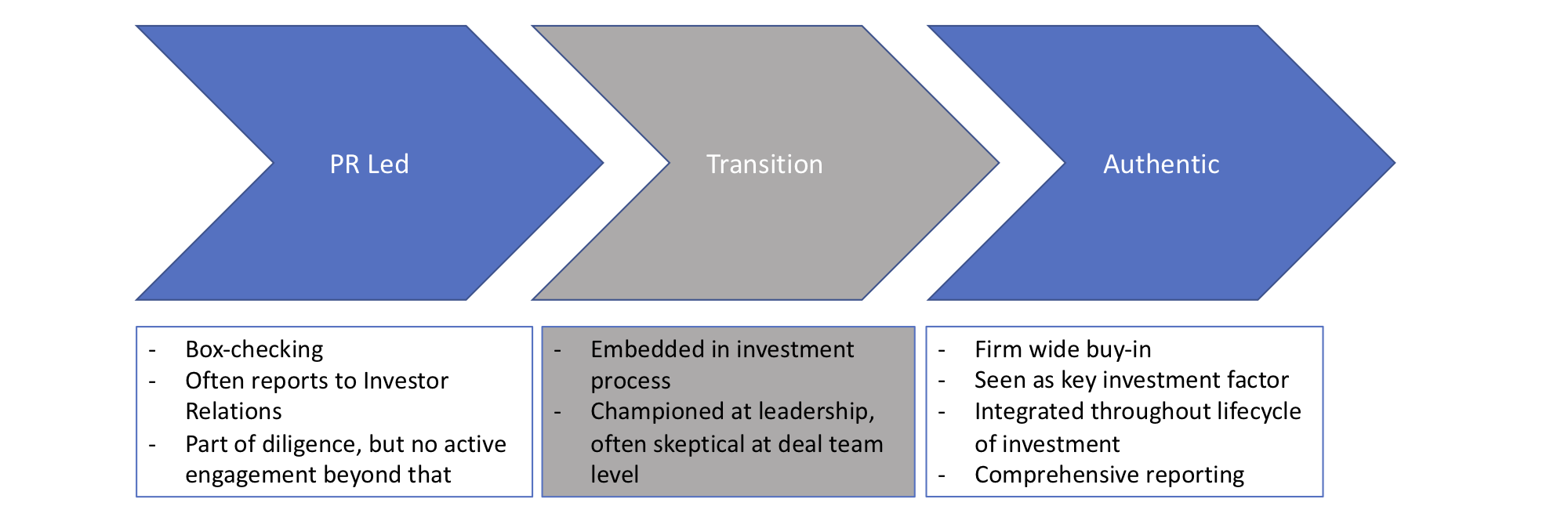

My second thought is that, the majority of investment firms and companies see ESG as a PR and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) exercise designed to deflect criticism that they are part of the problem in society. In surveying over a dozen leading Private Equity firms, I found that every single one admitted (when pressed) that they incorporate ESG principally because their investors expect it.

My third thought stems from returns being the (nearly) sole objective of many private equity firms. Under the current shareholder centric model, most investors remain singularly focused on driving returns and believe that ESG will (at best) be neutral if not negative to returns.

Shifting Viewpoints

And yet, a small but growing number of private market investors have found religion on ESG. What creates this mindset shift?

The Private Equity managers and companies that see ESG’s positive impact on their performance begin to embed it more thoroughly into the processes, culture and companies they touch.

Over the last few years, I’ve observed several funds make this transition. They initially adopt ESG solutions for stakeholder management (their LPs are asking for it), and as a box checking exercise. Over time, they realize that some of their best performing investments are scoring well on the ESG box checking. Gradually, they tease out the materiality of where ESG approaches could be value creating or risk avoiding, depending on the circumstances.

Indeed, I spoke with one senior partner at a fund that started embedding ESG around 2008 when a European partner pushed the idea to satisfy European LPs. The American partner I spoke with was pretty skeptical, but over the years, he’s seen the benefit it creates and he now is a full-fledged supporter of ESG being material in their investment factors.

Why has this been so hard?

I have quite a bit of empathy for firms trying to implement and adopt ESG standards and metrics in their work. ESG standards and metrics have been a moving target for several decades now, going back to the Global Reporting Initiative in the late 1990s.

- If you were an early mover a decade ago, you likely gravitated toward the Global Reporting Initiative(GRI) based out of the Netherlands.

- Then, a group of investors and industry participants got together and created a set of standards and metrics that were different from GRI under the Sustainable Accounting Standards Board(SASB). This new set of standards and metrics has increasingly gained traction and in the process, GRI and SASB have had a semi-public squabbling match over the relative value of their approaches.

- Other innovations and approaches followed, including the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures(TCFD). Every few years the best-in-class approaches are replaced.

There’s not a definitive answer yet. In fact, now the financial standards bodies are starting to ask if they should embed sustainability metrics in their financial accounting standards.

So what approach should a company or investor take?

This challenge is really what prompted the title of this article. ESG is gaining momentum, but we don’t yet have enough consistency or clarity to enable it realize its potential. It’s a journey in need of a destination.

The chart below highlights how there are lots of options to address this challenge.

Source: BrownFlynn/ERM

Not all ESG is spin

I admit to using a very broad brush in describing the investment community and associated companies’ ESG efforts. As previously mentioned, there are a growing number of companies and fund managers who are leading the way in developing best in class solutions for incorporating ESG in creating stakeholder capitalism over shareholder capitalism. But what I’ve found interesting is that they often invest ahead of where it’s proven that they will get returns. This seems to be driven by a few factors.

Living the values

First, they have developed a brand and relationship with customers built around values. The poster child for this is Patagonia, which has often done things first that are seen to be counter to their economic interest. The examples include:

- closing their stores on Thanksgiving to give their employees more time with their families

- running full page ads asking consumers to really think if they need more Patagonia gear before they buy it

- and investing heavily to have a repair and reuse facility that would prolong the life of goods that would not only add cost but also delay the higher margin contribution of new sales, etc.

And yet, the CEO (Rose Marcario) recently highlighted, “I think most of the companies that do that in a way that’s really consistent with their values are rewarded for doing it. This last decade has been the best decade for us in terms of business overall.”

Among fund managers, Bridges Fund Management exemplifies this philosophy. As I was doing diligence on one of their funds, a competitor referred to them as “the only PE firm that company owners consider acceptable to work with.” Their values-driven approach is authentic and long standing and highly valued by their Limited Partners. In some cases, they won bidding contests for companies without the highest bid, as they were the ‘acceptable’ firm to work with. Paying less than the competition is certainly one way to help returns.

Social license to operate

The second reason I’ve seen fund managers and companies embrace ESG is related to the above example of Patagonia but has a different angle. Namely, they invest in anticipation of changes in the formal and informal license to operate.

Formal changes would be new laws and policies that will require companies and investors to adopt these approaches. An example would be California SB 826 that requires companies in California to have at least one female board member. About 25% of corporations didn’t meet this criterion when the bill was signed into law in 2018. Companies are now spending time reworking their governance to accommodate this law, while groups that diversified early on haven’t been distracted by this new requirement.

An example of an informal license to operate relates to public pressure and consumer choice. A recent example is the focus on the negative effects of plastic in the oceans. A number of companies like Starbucks eliminated plastic straws (pre-pandemic at least) to help address this problem. Consumer sentiment and backlash against straws caused this reaction well ahead of any policy or legal response.

Unilever is another great example. They established time bound and quantifiable objectives to discontinue use of unsustainable palm oil, even though there’s no legal requirement to do that. The fact that they tied a sizable portion of the executive bonuses to hitting these sustainability metrics is an indication this was a core focus and not stakeholder management.

I see examples of funds responding similarly. A fund manager, who commented to me off the record, had an opportunity to invest in a successful business with a great product, great brand and a loyal and growing customer base. With limited geographic distribution it had huge growth potential and would be a fabulous financial return. But they passed on the opportunity as they felt the ESG factors would be hard to overcome. It turned out it was a confectionary company, and they felt that the growth in diabetes, obesity and health problems put this company on the wrong side of where a quality ESG company would need to be. Confectionary companies are unlikely to be illegal. They were more concerned with the social license to operate as the abundance of sugar in most diets is increasingly seen as a health challenge for society.

ESG positively affects returns

To my point above that returns will trump all else under the current shareholder centric model, those Private Equity managers and companies that see ESG as helping their performance are going to embed it more thoroughly into the processes, culture and companies they touch. A very concrete example of this is when I was speaking with a deca-billion dollar pension fund, who was thinking about their private market investments. The head of the pension had two concerns. First, he thought Carbon was going to be an issue. He didn’t know if it would be cap and trade or carbon taxes, and he didn’t really care, but he knew at some point carbon was going to become a liability. His second problem was that he felt the younger generation will care a lot about the products they buy and the products’ impact on the environment and society. In some ways, this is the social license to operate, but the reality is, he felt these were investment factors they needed to consider, as they will affect their returns. If he didn’t do this, they will wake up one morning and find their portfolio was massively underperforming, which is a huge problem for a pension with defined liabilities.

Hallmarks of good ESG investors

So if the high-level concepts (E, S and G) are well defined, but the specific metrics and definitions are still up for debate, what is the answer ? The answer is pretty qualitative and squishy. Yes, investors often publish an ESG report (or sustainability report or equivalent). They may list the UN Sustainable Development Goals their business touches. But that really doesn’t make it terribly actionable or ideal to compare firms.

One of the first hallmarks of strong ESG integration is the culture of the firm. The tricky part about this, is that many firms provide glossy reports and flowery language about how important ESG is in their culture and processes. To really verify this, you need to go a level deeper to see if their actions are more on the PR side or more authentic. At the very least though, if they don’t say anything about their culture embracing ESG, that’s typically not a great sign.

Secondly, it’s important to consider whether they have an internal person responsible for ESG and how their role is structured.

- Is the ESG ‘champion’ a partner-level role?

- Do they report to the Managing Partner or CEO of the firm? Or do they report to investor relations?

- Are they on the investment committee? Are they seen as a center of excellence’ that investment professionals can tap into, or are they integral to the investment team?

- Do they not have an ESG lead, as it’s expected to be driven by each investment professional?

The structure of how this is set up speaks quite a bit to whether they are more on the PR or Authentic end of ESG.

Processes

Firms should be able to articulate the framework they apply for ESG in their investment process, the standards and data associated within this framework, and have processes for transparency. I’d break it down into the below steps (and this isn’t that original as many ESG manuals talk about these needs):

- Intentionality – Do they identify ESG objectives at the beginning of an investment? Do they generate an ESG plan and goal at exit for each investment prior to deploying capital? If they invest first and then figure out what to measure later, that’s more on the PR side.

- Measurement – How do they track and iterate on the ESG plans they have set out? How are they measured and how is that data used to improve performance?

- Verification – How do they verify these metrics? Who are their auditors and how experienced are they with ESG? Are there any conflicts of interest in the audit process?

- Disclosure – How do they disclose these metrics?

On this last point, I think the best-in-class groups have several specific criteria in their disclosure. First, they are complete in their disclosure. Many funds, especially the really large ones, only talk about a handful of their portfolio companies. Not to imply they are cherry picking the best examples, but if they aren’t providing ESG data on every company it’s easy to conclude they are.

Second, they talk about what is going wrong and what’s underperforming. Most reporting is spun in the most positive light possible. And yet, nothing ever goes perfectly at every company. Indicating what’s going wrong actually enhances their credibility as opposed to making them look bad, provided it’s not every company in the portfolio.

Finally, they share what they are learning and how they are iterating to get better in thinking about ESG going forward. They may not share this level of detail in their website or their public ESG report, but they certainly should provide it to their investors. If they provide detailed financial information for each company at Annual General Meetings, they should provide ESG data for each company as well.

Conclusion

I believe there are quite a few funds that are engaging in ‘greenwashing ’ and are more PR driven in their ESG efforts. However, I’m encouraged that the authentic practitioners are growing in number from just a few like Acits and EQT, who have been at the forefront of ESG integration, to many more that are shifting from a box checking exercise to finding more value fully integrating ESG in their investment process.

The standardization of ESG data and frameworks remains somewhat illusive, so it’s not as simple as it seems. However, the focus and attention on standards is gaining momentum across multiple stakeholders and best practices are starting to emerge. Some of the groups like GRI and SASB are also starting to work together, which is the first step to rationalizing the options to define a gold standard. I’m cautiously optimistic that in the coming 1-3 years, agreement will be reached on quality frameworks and standards that will not only be material to performance and investor needs, but also will be easily implementable similar to how financial accounting is standardized today. However, I’d suggest that waiting until the rules are finalized will actually be more detrimental than trying to move down the continuum of integrating ESG. The later you start, the less credibility you have and the more catch up you’ll have to do as the standards crystalize. So, get started on your journey, the destination is just over the horizon!